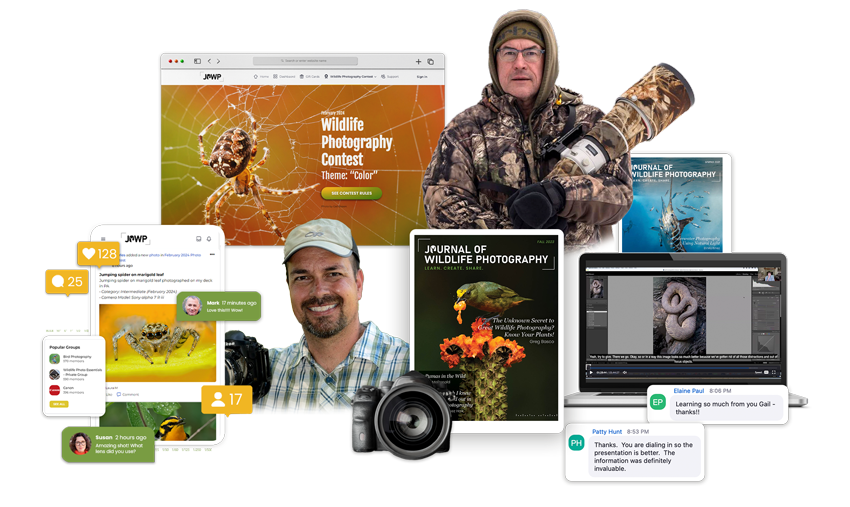

Join Now to Get Instant Access to This Content Plus You’ll Also Receive These Bonuses!

BONUS #1:

Monthly Live Webinar Trainings

Learn from Award-Winning Photographers in our Live Monthly Trainings.

As a member, you’ll get free monthly 90-minute trainings by award-winning professional wildlife photographers like Simon d’Entremount, Isaac Grant, Greg Basco and many more who dive deep into both beginner and intermediate topics. Directly following the trainings, the speaker will open up the floor for 30-minutes of Q&A. You’ll get instant access to all new and past trainings with your membership.

(Value $197.00/month)

Today: Included FREE

BONUS #2:

Monthly Live Photo Contest Image Critiques

Learn how to improve your photo contest entries.

We’ll choose 4 to 5 non-winning photos and provide detailed insights on how they could be improved and possibly win next time. Directly following the critique, we will open up the floor for 15-minutes of Q&A. You’ll get instant access to all new and past critiques with your membership.

(Value $197.00/month)

Today: Included FREE

BONUS #3:

Digital Magazine

Workshop-Level Education in an Easy-to-Read Quarterly Publication.

In 2019, the Journal of Wildlife Photography was created to bring wildlife photographers workshop-level training into the pages of a digital publication. With columns on conservation, macro photography, bird photography, animal behavior and habitats, underwater photography, DSLR and Mirrorless Autofocus systems, light and composition, and so much more.

(Value $97.00/year)

Today: Included FREE

BONUS #4:

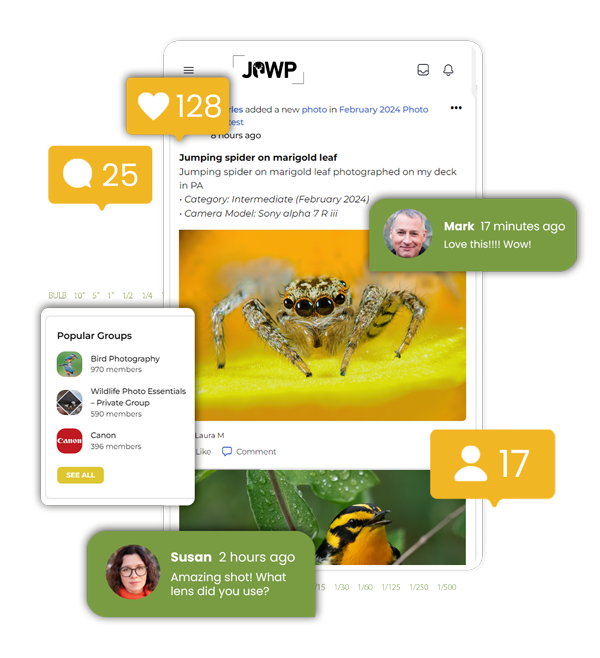

Social Community

Share Your Photos and Get “Real-Time” Feedback From Our Private Online Community.

Connect with other wildlife photographers, share your photos, and learn from award-winning professionals through live virtual workshops, training, and seminars. Receive personalized feedback from your peers and get valuable insights from image critiques by working professionals.

(Value $97.00/year)

Today: Included FREE

BONUS #5:

Article Library

In-depth Articles on Wildlife Ecology, Shooting Tips, Field Techniques, and More.

Explore topics such as animal behavior, habitat management, outdoor photography, and shooting skills, among others. Each article is carefully researched and written in an engaging style, making it easy to follow and understand. You’ll get instant access to all new and past articles with your membership.

(Value $97.00/year)

Today: Included FREE

BONUS #6:

Monthly Photo Contests

Every month, JOWP hosts themed photo contests with cash prizes of $500.

(Value $120.00/year)

Today: Included FREE

Join Today and Get Instant Access

- Monthly Live Webinar Trainings (Value $2364.00/year)

- Monthly Live Photo Contest Image Critiques (Value $2364.00/year)

- Digital Quarterly Magazine (Value $97.00/year)

- Social Community (Value $97.00/year)

- Article Library (Value $97.00/year)

- Entry into our monthly photo contests. (Value $120.00/year)

Total Value: $5139.00/year

LIFETIME

10 contest entries into every monthly photo contest.

ANNUAL PLUS+

5 contest entries into every monthly photo contest.

ANNUAL

1 contest entry into every monthly photo contest.